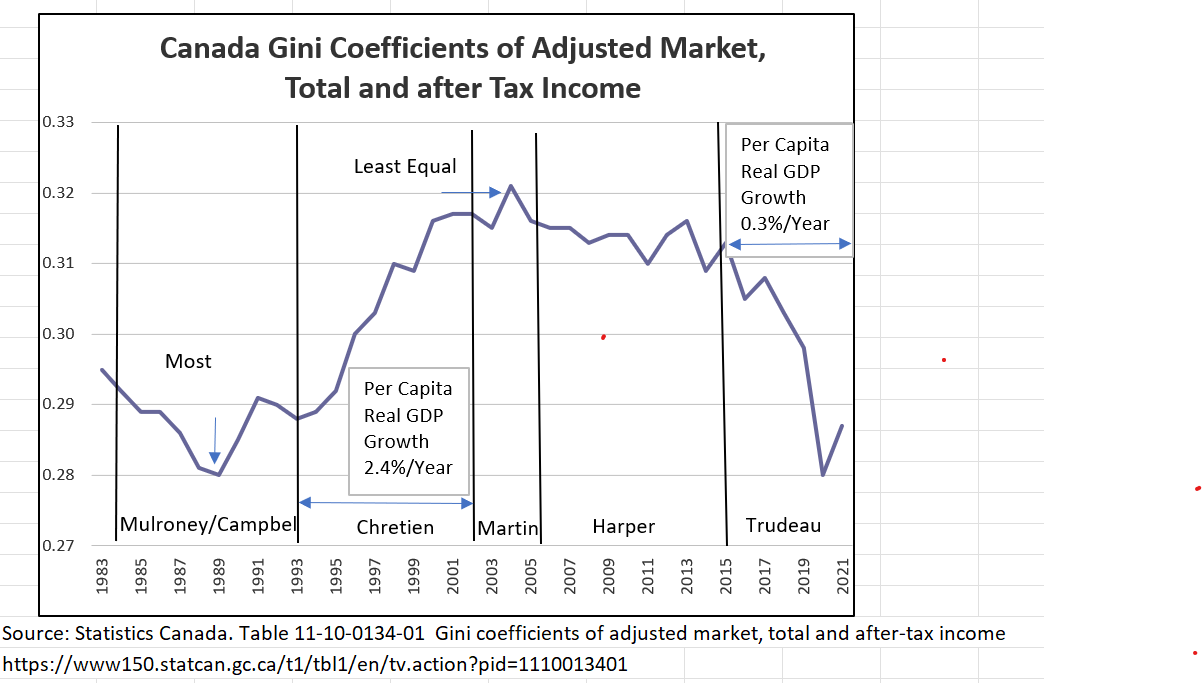

The most widely used metric of income equality is the Gini Coefficient, named for its inventor, the Italian statistician and sociologist Corrado Gini (1884-1965). The Gini coefficient takes the value zero when equality is perfect — everyone has exactly the same income or wealth — and is equal to one when one person has everything. Statistics Canada publishes Gini coefficients regularly. Their path over the years reveals some interesting facts that may be important in assessing the merit of the policy platforms of parties competing in upcoming elections.

From 2015, when the Trudeau government came

into office, through 2023 the Gini coefficient fell (from .314 to .288). That

means inequality fell and equality rose, which was the government’s plan. In

contrast, between 1993 and 2003, when Jean Chrétien was prime minister, the

Gini coefficient rose — from .289 to .316. Inequality rose, equality fell. That

probably wasn’t the government’s plan. But that is what happened.

Over these two periods, the growth in real per

capita income also differed — markedly. During the Chrétien years real per

capita economic growth averaged 2.4 per

cent per year. Under Trudeau it has averaged one-eighth that, just 0.3 per cent

per year.

Many factors determine the rate of economic

growth and degree of income equality in a country, too many to discuss here.

But it is useful to consider some differences in the legislative agendas

pursued by the two Liberal governments, Chrétien’s and Trudeau’s, that

economists consider relevant.

Chrétien’s policies were focused on

eliminating the large fiscal deficits he inherited on taking office in 1993.

They did so by reducing spending on social transfers, including by restricting

eligibility for and the generosity of employment insurance. Such measures

likely affected the incomes of the poor and may well have increased income

inequality. Cuts to the civil service, streamlined regulation, replacing income

taxes with value-added taxes (i.e., the GST) and encouraging free trade all

reduced the role of government in the lives of Canadians and strengthened the

role of markets and incentives in the economy. The reforms generally were not

as drastic as their opponents claimed but their effect was real.

In contrast, Justin Trudeau’s

policies have focused on equalizing incomes and preventing climate change and

they have substantially increased the role of government in the economy by

raising social security spending and subsidies to individuals and businesses,

increasing regulations and raising taxes, especially at the top end. To

administer all the new spending and regulation, the civil service has expanded

rapidly.

In short, increased reliance on markets, which

Chrétien’s policies brought about, raised income and inequality. On the other

hand, reducing the role of the market economy, as Trudeau’s policies have done,

increased equality but has also reduced economic growth. These correlations,

though simple and without further analysis mainly suggestive, are consistent

with economic theory and historical experience.

It’s also interesting to look at what happened

to the self-assessed happiness of Canadians during the two periods. Both

governments presumably wanted to raise happiness, but during Chrétien’s time

the index of happiness rose from 6.8 to 7.1 on a scale of one to

10 while during the Trudeau years it has fallen — from 7.4 to 6.9.

All sorts of things presumably affect how

happy people are feeling. The negative effects of dealing with both the

pandemic and climate change may well have contributed to the decline in

well-being among Canadians during the Trudeau years. On the other hand, those

were global phenomena so they don’t explain why Canada fell from fifth to 15th

happiest country among 135 countries ranked.

These changes in happiness in the two periods

are a puzzle. Income is an important determinant of happiness and there are

more subsidized poor Canadians than there are taxed rich Canadians, which

suggests average income equality and happiness should have risen together as

the Trudeau government raised taxes on the few and increased subsidies for the

many. That happiness fell instead may be the result of policies that have

affected Canadians’ lives for the worse but not brought offsetting benefits:

environmental and other regulations, increased taxation, inflation and,

finally, rapid immigration that has contributed to housing unaffordability and

the overcrowding of health care and other public facilities.

In addition, a new source of unhappiness may

have resulted from innovative policies that have worsened the inter-personal

relationships that research has found

to be “the most significant predictor of overall happiness, life satisfaction, and wellbeing.” These

policies encouraged the formation of identity groups based on sexual

preferences, skin colour, ethnic origin, age and gender.

The rationale for such policies is found in

Karl Marx’s theory that under capitalism the bourgeois owners of property

oppress the proletariat of labourers, which leads to an ever-growing gap in the

income of the two groups. This idea has now morphed into the “woke” view that

the below-average incomes of members of identity groups are caused by the

oppressive, discriminatory policies of other Canadians, but mainly white males.

To eliminate the effects of this

discrimination and raise the equality of income the Trudeau government has

imposed “diversity, equity and inclusion” (DEI) requirements in Canadian

organizations and institutions. Such requirements can involve preferential

employment, student admission, salary benefits and promotions and so on, all of

which come at the expense of Canadians who find that merit as the primary

determinant of success is now replaced by the possession of personal

characteristics whose value is rewarded by bureaucracies.

The adoption of DEI policies has led to what

very likely are happiness-decreasing divisions among Canadians in general,

among identity groups and even among the members of such groups, who may have

expected more benefits than the system has brought them. Dissatisfaction and

division resulting from these “woke” policies may help explain the decline of

happiness among Canadians.

Let us hope voters consider all this when they

assess the merit of competing parties’ platforms in upcoming elections.

Herbert Grubel, professor emeritus of

economics at Simon Fraser University, was MP for Capilano-Howe Sound 1993-97.

This article was published in Canada's Financial Post on May 21, 2024, without the graphs below.

.jpg)